Rising Political Temperatures in South-Eastern Europe’s Energy Sector

The political landscape in South-Eastern Europe continues to heat up, driven by the increasing likelihood of disruptions to Russian gas transit through Ukraine, sanctions targeting Gazprombank and other Russian financial institutions, and a frantic search for solutions to maintain Russian gas imports via Turkey and the TurkStream pipeline. The urgency of this issue was underscored at a recent energy forum in Istanbul, hosted by Turkey’s energy minister and attended by President Erdoğan, energy ministers from Azerbaijan, and officials from countries along the TurkStream route. Discussions and agreements reached at the forum reveal both the intensity and the direction of these efforts as countries race to implement solutions before the year’s end, with Ukraine poised to cease gas transit.

Key Challenges

Optics and Morality

The TurkStream coalition, led by figures like Erdoğan and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, frames its actions as matters of energy security and economic necessity. Yet these efforts are increasingly viewed as anti-Ukrainian, particularly against the backdrop of Russia’s war on Ukraine. Russia’s ongoing attacks on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, seen by some as an “Energomor” reminiscent of the Holodomor, make the continuation of TurkStream morally contentious. Most EU nations have managed to wean themselves off Russian oil and piped gas, proving that the insistence on maintaining Russian energy ties often stems from political expediency rather than necessity.

The TurkStream project has entrenched a level of interdependency between regional leaders and the Kremlin, creating long-term geopolitical and domestic political repercussions that will shape the region’s agenda for years to come.

Impact of U.S. Sanctions

U.S. sanctions against Gazprombank aim to curb Russia’s ability to manipulate gas prices and maintain dominance over South-Eastern Europe’s energy market. Kremlin’s gas price undercutting also inhibits the profitability of importing liquefied natural gas (LNG), including from the United States, as Gazprom can leverage its gas price to maintain its market position. This creates significant challenges for Bulgaria, where transit revenues account for nearly 80% of Bulgartransgaz’s income, with 90% of gas flowing through its pipelines originating from Russia. These calculations are based on BTG’s gas traffic data.

Bulgaria’s energy policies remain heavily influenced by a small group of decision-makers, notably caretaker Energy Minister Vladimir Malinov. Despite public disagreements among political leaders, coordination between figures like Boyko Borissov, Delyan Peevski, and President Rumen Radev has ensured that Bulgaria’s dependence on Russian gas transit remains unshaken.

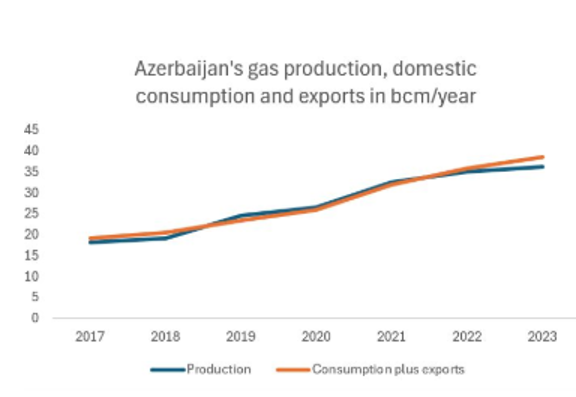

Alternative Supply Limitations Azerbaijan has emerged as a potential alternative supplier, but its ability to offset Russian gas is constrained by existing contractual commitments and limited infrastructure. Moreover, suspicions persist that some Azeri supplies might serve as rebranded Russian gas. While the EU is currently tolerant of Azerbaijan’s growing role, this tolerance has limits and could pose long-term reputational risks for Baku.

An interesting reference to a study on the potential of EU-Azerbaijan energy cooperation and its impact on the EU’s gas dependence on Russia by Gubad Ibadoghlu, Senior Visiting Fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science and Ibad Bayramov Analyst at Morgan Stanley, reveals a growing disparity between Azerbaijan’s production, on one side, and consumption and export volumes, which raises additional suspicions about Russia-Azerbaijan potential backdoor deals.

Bulgaria’s Critical Role

Bulgaria occupies a pivotal position in the SEE’s energy network, serving as the primary entry point for Russian gas in the EU starting in 2025. However, its energy strategy is driven by transit revenues rather than consumer interests or energy security. This over-reliance on Russian gas has stifled domestic exploration, alternative sourcing, and infrastructure development, including LNG storage capacity. The Chiren gas storage expansion project, now two decades old, aims to increase capacity from the current 0.55 billion cubic meters to 1 billion cubic meters. However, progress has stalled once again, even sabotaged, undermining LNG’s competitiveness against Russian pipeline gas. Such decisions are symptomatic of Bulgaria’s broader dependency on Moscow’s energy policies. Efforts to secure exemptions from U.S. sanctions on Gazprombank have fallen largely to Turkey and Hungary, with no guarantees of success.

Wider Implications

The actions of the TurkStream coalition risk creating a “gray zone” within the EU gas market, where Russian gas continues to dominate despite Brussels’ initiatives to diversify energy supplies. Leaders like Viktor Orbán and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan have openly criticized EU and US sanctions and sought to increase imports of Russian gas, undermining EU cohesion and entrenching dependence on Kremlin-controlled energy.

Beyond the scope of TurkStream and natural gas, the potential sale of Lukoil’s Burgas oil refinery—possibly to Hungary’s MOL—raises alarms about a broader geopolitical strategy by the Kremlin. This maneuver could leverage ostensibly EU-aligned entities to maintain Russian energy dominance. Hungary’s involvement in the refinery deal suggests coordinated efforts with Orbán’s TurkStream allies in Bulgaria to perpetuate Russian influence while navigating and circumventing EU regulatory constraints.

The coming months will determine whether South-Eastern Europe can break free from its reliance on Russian energy or remain entrenched in dependency. As year-end deadlines loom, the region’s leaders face mounting pressure to navigate a volatile landscape where economic, political, and moral considerations are increasingly intertwined.

Ilian Vassilev