Potential and Challenges of the Vertical Gas Corridor

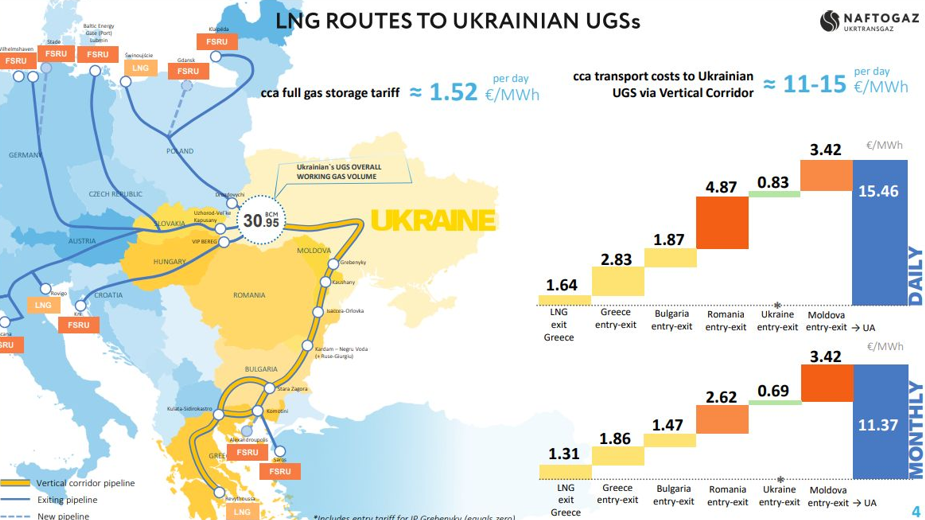

Ukraine’s urgent need for at least 6 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas imports to meet its 2025–2026 heating season demands has brought energy security into sharp focus. As Ukraine seeks to diversify away from Russian gas amid ongoing geopolitical tensions, the Vertical Gas Corridor (VGC)—a pipeline network linking Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, Hungary, Slovakia, and Ukraine—offers a promising but underutilised solution. The VGC’s success depends on robust infrastructure, strategic investments, and overcoming entrenched commercial interests, high transit tariffs, and political inertia that continue to favor Russian gas flows.

The Northern Route: Poland’s Model of Energy Solidarity

Poland’s northern gas supply route to Ukraine exemplifies reliability and strategic alignment in Eastern Europe’s energy landscape. Committed to the European Union’s goal of phasing out Russian energy by 2027, Poland has taken bold steps to support Ukraine while reducing Kremlin revenues. By halting gas transit through the Yamal–Europe pipeline, Poland forwent transit fees exceeding $500 million, prioritizing energy independence and solidarity with Ukraine amid ongoing Russian aggression.

In April 2024, Poland’s state-owned Orlen and Ukraine’s Naftogaz signed a landmark agreement to supply 100 million cubic meters of liquefied natural gas (LNG) via Polish infrastructure. Though modest in volume, this deal highlights the route’s potential as a conduit for non-Russian gas. Poland’s competitive transit tariffs—lower than those of southern routes—enhance its appeal. Investments in LNG terminals, such as the Świnoujście facility, and interconnectors with neighboring countries have strengthened Poland’s position as a regional energy hub, providing Ukraine with a stable, geopolitically aligned supply channel.

The Southern Route: A Missed Opportunity

In stark contrast to the northern route through Poland, the southern corridor—anchored by the Trans-Balkan Pipeline and the Vertical Gas Corridor (VGC)—remains severely underutilized, despite possessing a reverse-flow capacity of over 17 billion cubic meters (bcm) annually. This infrastructure has the technical potential to deliver non-Russian gas to Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and the Western Balkans, reshaping the region’s energy landscape. Yet several structural and political obstacles continue to undermine its viability.

First, prohibitively high entry-exit tariffs in Romania and Moldova make LNG imports via the southern route economically uncompetitive. These tariffs, often significantly higher than those in Poland, discourage traders from choosing the VGC for non-Russian gas shipments, despite the strategic importance of diversification.

Second, Bulgaria has reserved large portions of the Trans-Balkan Pipeline’s capacity—particularly between Compressor Stations Lozenets and Provadia—for Russian gas transiting via TurkStream. This effectively sidelines key infrastructure segments, such as the Kardam–Negru Vodă 2 and 3 pipelines, paralyzing the corridor’s potential to function as a capacity-integrated, open-access route for alternative gas supplies.

Third, although over €280 million in funding is earmarked for VGC infrastructure improvements in Bulgaria alone, the track record of the national gas transmission operator Bulgartransgaz raises serious concerns. Previous capital-intensive projects—most notably the TurkStream extension and the delayed expansion of the Chiren underground gas storage facility—have been marred by budget overruns and suboptimal performance. If these trends continue, the VGC risks becoming another case of overspending with minimal returns, and a rising debt burden unsupported by future transit revenues.

A test transaction in March 2024 between Ukraine’s DTEK and U.S.-based Venture Global demonstrated the technical feasibility of importing liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Greece. However, only 10% of the cargo reached Ukraine, with the remaining volumes sold to Greek traders. The episode exposed not only commercial inefficiencies but also logistical and coordination shortcomings. Nonetheless, a follow-up agreement signed in June 2024—valid through 2026 with a potential 20-year extension—signals DTEK’s long-term strategic interest in leveraging Greek LNG terminals, provided that systemic barriers are addressed.

Turkey’s expanding LNG infrastructure—anchored by the Marmara Ereğlisi and Aliağa terminals—offers additional promise for regional diversification. These facilities could enable increased volumes of non-Russian gas to be routed northward via the Trans-Balkan Pipeline’s reverse mode. However, absent a coherent regional strategy and streamlined regulatory alignment, this potential remains largely untapped.

Support Independent Analysis

Help us keep delivering free, unbiased, and in-depth insights by supporting our work. Your donation ensures we stay independent, transparent, and accessible to all. Join us in preserving thoughtful analysis—donate today!

Russian Gas and TurkStream: A Structural Challenge

Despite the European Union’s stated objective of phasing out Russian fossil fuel imports, Moscow continues to maintain a powerful presence in Southeast Europe through the TurkStream pipeline. This infrastructure sustains both commercial and political dependencies that hinder diversification efforts. Russian gas, priced below the Dutch TTF benchmark, remains highly attractive to traders. Much of it is resold into Central Europe or redirected to Ukraine via Hungary and Slovakia, creating a web of secondary flows that disincentivizes direct imports of LNG or pipeline gas through alternative routes like the VGC.

Recent developments in Bulgaria have intensified concerns. The widely publicized groundbreaking for new pipeline loops near Kresna—organized by Bulgartransgaz—was promoted as a milestone for expanding VGC capacity. Yet, the failure of the first short-term capacity auction for “Route 1”—intended to offer integrated, non-Russian capacity from Greece’s Revithoussa terminal to Isaccea, Romania—exposed a stark disconnect between system operators and market demand.

As of mid-2025, only 2.9 million cubic meters per day of non-Russian LNG are being transported via the Vertical Gas Corridor—barely 5% of the more than 60 million cubic meters of Russian gas that transit daily through Bulgaria. This imbalance calls into question the political will and commercial incentives underpinning diversification. It also lends credence to growing concerns that diversification discourse may serve as a cover for expanding Russian gas transit. With Gazprom reportedly planning to sell an additional 10 bcm in the region over the next three years, the gravitational pull of TurkStream is likely to continue shaping Bulgaria’s energy policy more than any Brussels-backed alternatives.

Unless addressed through decisive regulatory reform, transparent infrastructure governance, and greater regional coordination, the southern route may remain a missed opportunity—technically promising but politically constrained, and ultimately reinforcing rather than breaking Europe’s energy dependence on Russia.

Barriers to True Diversification

Achieving genuine energy diversification in Southeast Europe requires far more than physical infrastructure. It demands regulatory reform, market transparency, and a level playing field. Today, several key challenges continue to undermine the transformative potential of the Vertical Gas Corridor (VGC).

1. Distorted Tariff Structures:

In 2025, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, and Moldova introduced a “super-integrated” tariff for Route 1, effectively halving transit costs for non-Russian gas. While this was a positive step, Russian gas continues to enjoy preferential access and tariff treatment across several VGC countries, skewing competition and reinforcing Gazprom’s dominance.

2. Price Indexation and LNG Competitiveness:

The economic appeal of LNG depends heavily on how it is priced. When indexed to the U.S. Henry Hub—plus premiums for transport and insurance—LNG can compete with Russian pipeline gas. However, many contracts remain tied to the more expensive Dutch TTF index, a legacy pricing model that benefits large European and American ‘demand integrating’ firms profiting from arbitrage between Henry Hub and TTF. This pricing misalignment discourages secondary traders from prioritizing non-Russian LNG, particularly during periods of tight margins.

3. Infrastructure Failures and Transparency Gaps:

The abrupt shutdown of the new floating LNG terminal in Alexandroupolis—just weeks after it began operations in 2024—raised serious concerns. Officially attributed to technical issues, the outage conveniently curtailed LNG imports during the 2024–2025 summer injection season and the critical winter period. As shareholders in the project, Bulgartransgaz, DEPA and DESFA have remained silent on both financial losses and recovery timelines, further eroding trust in their role as a neutral facilitators of diversification and promoters of the VGC.

4. Geopolitical Fragmentation:

The VGC’s effectiveness is hampered by divergent national priorities. Poland, for example, aligns closely with EU strategic objectives to reduce dependency on Russian gas. In contrast, countries like Hungary and Bulgaria appear more focused on maximizing transit revenues from Russian gas flows. This geopolitical misalignment complicates regional coordination and weakens the corridor’s strategic coherence.

Bulgaria’s Compromised Role

As the central node in the southern gas corridor, Bulgaria holds enormous strategic leverage—but it is caught in a web of contradictions. Through TurkStream, Bulgaria facilitates over $12 billion annually in revenue for Gazprom, cementing its position as a key transit state for Russian gas into Europe.

Under Vladimir Malinov as Bulgartransgaz CEO, the company has prioritized preserving this role over enabling diversification. Key infrastructure—such as the Trans-Balkan Pipeline’s full reverse-flow capacity—remains underutilized for non-Russian gas. Delays in the Chiren gas storage expansion, minimal capacity allocation for LNG, and opacity around the Alexandroupolis terminal failure all point to a broader trend: Bulgaria is acting less like a neutral transit hub and more like an active broker of Russian energy interests.

This position is increasingly at odds with the EU’s target of eliminating Russian gas imports by 2027. Bulgaria’s hesitation to fully liberalize its transmission system raises fundamental questions about whether its leadership is deliberately safeguarding Gazprom’s market share in order to preserve national transit revenues. The very funding and construction of TurkStream—pursued five years after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and amid its continuing war on Ukraine—underscores the disconnect between Bulgaria’s infrastructure choices and the EU’s geopolitical priorities.

A Reality Check for the Vertical Gas Corridor

The Vertical Gas Corridor has the potential to be a game-changer for energy security in Ukraine and Southeast Europe. But that potential remains unrealized. So far, market dynamics have favored the cheapest option—Russian gas—and traders will continue to fill available capacity accordingly. Without viable, economically competitive alternatives, the VGC will remain structurally aligned with the very dependency it was meant to disrupt.

Poland offers a model of what is possible when infrastructure investment is guided by clear geopolitical principles, followed by successful business models for Russian gas displacement. Bulgaria, on the other hand, stands at a crossroads. It can either embrace its strategic role in Europe’s energy transition or remain a geopolitical bottleneck, enabling Moscow’s continued leverage over European energy markets.

Until these contradictions are addressed head-on, the Vertical Gas Corridor will remain more promise than reality—an ambitious blueprint overshadowed by the enduring pull of Russian gas and the inertia of entrenched interests.

Ilian Vassilev