Under the Guise of the Vertical Gas Corridor, BTG BuildsPipelines to Serve an Oligarch

In recent years, the so-called “Vertical Gas Corridor” (VGC) has been promoted as a cornerstone of Bulgaria’s, the region’s, and Europe’s energy strategy—aimed at strengthening energy security and enhancing regional connectivity. Yet the support of Borissov-Peevski’s tandem for the actions of Vladimir Malinov, Executive Director of Bulgartransgaz (BTG), raise serious concerns about the project’s real objectives. Why is BTG prioritizing its domestic gas infrastructure expansion plans under the VGC flag that have no tangible link to boosting transmission capacity at Bulgaria’s key exit points toward Ukraine or Slovakia?

Support Independent Analysis

Help us keep delivering free, unbiased, and in-depth insights by supporting our work. Your donation ensures we stay independent, transparent, and accessible to all. Join us in preserving thoughtful analysis—donate today!

While the public is distracted with expansion efforts near the Greek border, the actual bottleneck lies in the 63-kilometer segment between Rupcha and Vetrino. Investment there would immediately enable reverse flow of up to 15 billion cubic meters of gas annually through the underutilized Trans-Balkan Gas Pipeline (TBP)—a move that would far surpass the marginal impact of the much-hyped “first phase” of Route 1 of the VGC or the East Maritza Basin gas connection.

Missed Opportunities and Misplaced Priorities

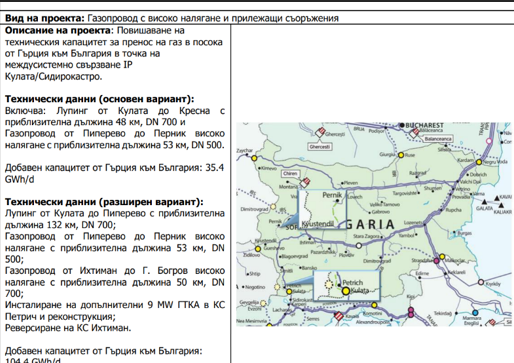

A technical assessment of entry capacity from Greece—via the Interconnector Greece–Bulgaria (IGB) and the Sidirokastro–Kulata route—reveals over 3 billion cubic meters of unused capacity annually, equivalent to 8 million cubic meters per day. This dwarfs the 2.9 million cubic meters per day that BTG claims can be engaged at Sidirokastro–Kulata to supply Ukraine.

Why, then, is Malinov so focused on highly publicized projects such as the “looping” from Kulata to Piperevo and a new pipeline from Piperevo to Pernik?

More critically: what strategic relevance does a pipeline to Pernik have to the Vertical Gas Corridor?

Note the proposal by a group of Bulgarian MPs, spearheaded by Delyan Dobrev—whose ties to Kovachki are evident and backed by a Peevski-aligned MP—to incorporate Kovachki’s TPP “Brikel” and TPP “Maritsa 3” (Dimitrovgrad) into Bulgartransgaz’s 825-million-BGN gas supply project for the East Maritsa Basin, under the pretext of expanding the Vertical Gas Corridor. This move persists despite AES (TPP “Maritsa East 1”) and ContourGlobal (TPP “Maritsa East”) having no plans to gasify their units. Strikingly, no active project exists for transitioning the state-owned TPP “Maritsa East 2” to natural gas, yet both of Kovachki’s plants have such initiatives underway. The MP proposal’s proponents further mandate the Minister of Finance to increase Bulgartransgaz’s capital by nearly 450 million BGN, effectively securing public funds for these ventures cloaked as part of the Vertical Gas Corridor.

These projects serve local distribution needs rather than regional energy security goals. They are disconnected from Bulgaria’s stated commitments to EU strategies, particularly increasing gas transit capacity toward Ukraine. Instead, they appear designed to serve narrow private interests—obscured by lofty rhetoric about European gas market needs and geopolitical alignment.

Cui Bono?

To uncover the real motivation behind these investments, we must ask: who stands to gain?

The answer lies in looking at the project dossier along the Piperevo and Pernik route, where two major potential gas consumers—Bobov Dol Thermal Power Plant and Toplofikatsia Pernik—are preparing to shift from coal to gas. Both are owned by Hristo Kovachki, a politically connected oligarch recently implicated in a corruption investigation by the Anti-Corruption Fund.

Judging by the technical specifications—pipe diameter, pressure levels, and design—these VGC-branded projects seem custom-built to meet the needs of Kovachki’s operations. Crucially, they relieve his companies of the financial burden of building their own compression infrastructure, a cost other market players must bear.

Two particularly troubling facts stand out.

First, according to recent BG Elves revelations, Kovachki—through his company TIBIEL—has attempted to negotiate the direct import of over 1 billion cubic meters of Russian gas via Turkey, both before and after the termination of Bulgaria’s gas state company Bulgargaz with Gazprom. Even a casual observer can see that such behind-the-scene efforts in the midst of geopolitical confrontation, backed by Magnitsky sanctioned patrons, run counter to Bulgaria’s national interests.

Secondly, this is not the first attempt of its kind. Years ago, on the eve of the South Stream saga, Delyan Peevski—then acting as Ahmed Dogan’s political enforcer—pursued a similar scheme with Gazprom involving the Varna TPP. The formula in both cases is identical: a transition from coal to gas based on two conditions—access to cheap, long-term gas contracts and someone else covering the infrastructure costs. Once again, BTG steps in to deliver, channeling public funds under the guise of supporting the Vertical Gas Corridor.

Geopolitical Theater or Private Gain?

BTG’s narrative casts the VGC as a driver of energy diversification and regional cooperation. In practice, however, the project echoes the failed promises of “Balkan Stream”—another initiative championed by its CEO Malinov. Marketed as a pathway to energy independence, The Balkan Stream instead deepened Bulgaria’s reliance on Russian gas—from 80% before TurkStream to over 90% today. Malinov’s excuse: “we tried, but the market chose Russian gas.” The same adage goes today.

Now, under the guise of energy security and solidarity with Ukraine, hundreds of millions of euros—including EU funds—are being funneled into infrastructure that overwhelmingly benefits private interests. Once again, the EU’s strategic goal of reducing dependence on Russian gas is being subordinated to opaque domestic agendas.

Institutional Facade and Political Protection

The behavior of state institutions in recent months has further exposed the entrenched power of Kovachki and his allies. When the Anti-Corruption Fund publicized its investigation into Kovachki’s energy cartel, the ruling coalition took extraordinary measures to block a parliamentary debate. The Energy and Water Regulatory Commission (EWRC) swiftly issued a statement declaring there was “nothing irregular” in the case—without offering any evidence, analysis, or due process.

This is not mere institutional inertia. It is active protection of vested interests amid a high-stakes power struggle for control over billions in euro in energy sector revenues. “Old players” resisting the rise of new political power centers—might be squeezed out. Peevski, now the de facto energy czar, is asserting control. Borisov, meanwhile, remains in the shadows—unable to stop the shift, but unwilling to challenge it publicly.

Transparency or More of the

The Vertical Gas Corridor is sold to the public as a vehicle for energy independence and a key route for gas supply to Ukraine. But its current trajectory raises serious doubts about its real purpose. Instead of investing in the strategically vital Rupcha–Vetrino segment of the Trans-Balkan Pipeline, which would unlock massive regional capacity, public funds are being diverted to projects that disproportionately benefit a select few.

This is a familiar pattern in Bulgarian energy policy: private deals cloaked in national or European grand branding.

The Need for Accountability and Strategic Vision

Bulgaria stands at a crossroads. Its energy policy could position the country as a genuine regional leader and partner in Europe’s energy transition—but only if transparency, accountability, and long-overdue institutional reform are pursued.

The public deserves a clear answer: Who benefits from Malinov’s version of the Vertical Gas Corridor? And why are public resources once again being used to serve private gain?

Ilian Vassilev