Russia blocks the Black Sea — NATO has no response. Yet.

Russia has threatened to treat all vessels on the Black Sea bound for Ukrainian ports as potential carriers of military cargo and therefore legitimate targets. Few people realise quite how much of an escalation that might be. Let’s hope those few include the worthies from NATO and its member states set to confer with the Ukrainian leadership tomorrow. And especially let’s hope Turkey’s ambiguous president Recep Tayyip Erdogan is thinking clearly about the common interests – and his own.

As Russian president Vladimir Putin’s Ukraine adventure goes from disaster to disaster, his minions react by coming out with scarier and scarier utterances. One recent example is a statement that emanated on July 19th from Russia’s Ministry of Defence (MoD), which is headed by that well-known Putin crony (and underperformer) Sergey Shoigu. Which might be even scarier than it seems at glance.

In this statement, the MoD announced that “all vessels travelling in the waters of the Black Sea to Ukrainian ports will be considered as potential carriers of military cargo”, and therefore considered legitimate targets for attack. Now, that in itself constitutes a major escalation of the war and a direct challenge to NATO, as it logically amounts to a Russian claim to control marine traffic along the coast of Black Sea states that are members of NATO – namely, Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey.

But there’s worse. Mr Shoigu’s ministry warns that, accordingly, the flag countries of such vessels will be considered to be involved in the Ukrainian conflict on the side of the Kiev regime. Moreover, continued the MoD, the effective blockade does not only affect only the Ukrainian parts of the Black Sea, but also “a number of maritime areas in the north-western and south-eastern parts of the international waters of the Black Sea”, effectively parts of the economic zones of Turkey, Bulgaria and Romania, which are “declared temporarily dangerous for navigation”.

Later on, Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) stepped back a little from its uniformed friends’ rather trigger-happy original version of the threat, instead asserting the right of the Russian Black Sea Fleet to inspect any vessel in the Black Sea area that is considered a potential carrier of military cargo for Ukraine. “Russia will inspect all ships in Black Sea waters before destroying them,” said Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Vershinin. “We have to make sure that the ship is coming with something bad, which means investigation, inspection if necessary, to make sure whether it is or not.”

Well, that’s very reassuring, Mr Vershinin, so thanks for that. But it should be noted that there’s a lot else that hasn’t been the subject of MFA back-pedalling. Notably the fact that the blockade affects not only Ukraine’s territorial waters, but also the so-called “safe” or “humanitarian” corridor. That is, the corridor– including the Danube Estuary – that, on July 20th, was declared closed for shipping via Bulgarian and Romanian territorial waters, despite being indeed kept open throughout the war, so far.

Two other points might also be remarked before we move on:

- First, and somewhat pedantically: even if the blockade had been confined to Ukrainian territorial waters, that would not have resolved all ambiguities, since Russia’s annexation of Crimea and recent hostilities would presumably mean that not everyone agrees on the definition of those waters

- Second, Russia’s sea blockade would not affect Ukraine alone. It would affect all Black Sea traffic, since it would raise the cost of shipping insurance in the region. It would also affect oil and gas drilling and production in this rather promising region, since often insurance companies react to such risks by simply refusing to cover drilling work. On top, mines drift along the coastline of Romania and Bulgaria.

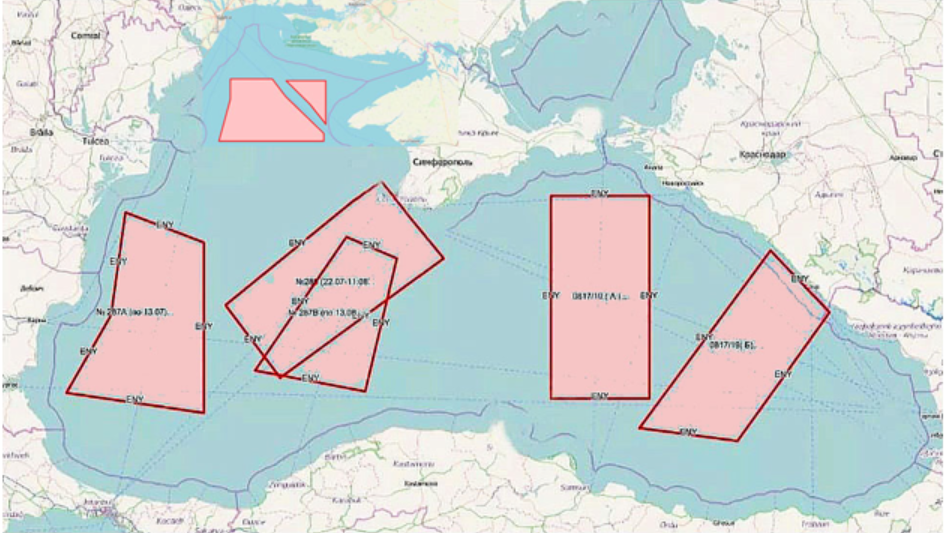

Now, this is not the first time Russia has threatened to control the Black Sea. It has been doing so for many years – centuries indeed. Lately it has been doing so by means of regular Black Sea Fleet drills and test firings of sea-launched missile, immediately before the attack on Ukraine on February 24th, 2022 (see map below). And NATO’s response, all along, has been too little, too late. Which has encouraged the current round of hard talk from President Putin.

In 2016, admittedly – once NATO had been awakened by Mr Putin’s annexation of Crimea – there was an attempt at a summit of the alliance in Warsaw to create a NATO naval force in the region. This, however, was blocked by – who else? – the then Bulgarian prime minister Boyko Borissov, who said, with characteristic whimsy, that he preferred to see tourist ships and sailing boats on the Black Sea. This fearless championship of leisure pursuits made Bulgaria the only one of NATO’s three Black Sea members to dissent from the initiative, though that was enough to block it.

And it came four months after a get-together that Mr Borissov seems to have taken more seriously. This was his crucial meeting, at the end of February 2016, with Lt-Gen Leonid Reshetnikov (late of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service, a successor of the Soviet-era KGB). Mr Reshetnikov has for many years served as Mr Putin’s Balkan expert and as his (none-too-secret) “secret envoy”, and at this meeting the limits of Bulgaria’s future “freedom of action” within NATO were discussed and agreed. With some effect, it seems…

Bulgaria’s objection to the Joint NATO Black Sea Naval Force was not the sole outcome of the new Putin-Borissov 2016 rapprochement. A year later, Mr Borissov and the newly elected Bulgarian President Rumen Radev implemented Putin’s most important geostrategic project in Europe, the Turkish Stream pipeline. Now called “Turk Stream”, this is an achievement of which – if pride were the appropriate emotion – Messrs Borissov and Radev could be very proud indeed. For, unlike its North European sister Nord Stream, Turk Stream is still carrying Russian natural gas to EU countries to this day.

These articles, analyses, and comments are made possible thanks to your empathy and contributions, which are the only guarantors of independence and objectivity in our work. The Alternatives and Analysis team.

The grain deal and the end of humanitarian corridors

The end of the grain deal on July 18th, raised the prospects of direct NATO-Russia confrontation in the Black Sea considerably. Russia’s massive missile attacks on port infrastructure linked to Ukrainian grain exports made it clear that Russia was prepared to destroy not only Ukraine’s infrastructure and storage facilities, but any merchant vessel it judged to be destined to a Ukrainian port. This effectively means a complete naval blockade of Ukraine and the transformation of the Black Sea into a Russian internal sea. Mr Putin is carefully picking his areas for a direct exchange with NATO and the Black Sea seems to offer him his best chance.

NATO countries are reacting cautiously. The White House has literally said that it has not yet decided how to respond. At this stage, the hypothesis of a military escort of civilian ships, is complicated to implement and the US is looking to Turkey for leadership in the process. This seems to reward Putin’s policy of poker.

Realistically, the restrictions on non-Black Sea countries’ vessels to access the Black Sea, that the 1936 Montreux Convention imposes, undermines NATO’s ability to project its power, as the Alliance cannot use its full naval capabilities to defend its member states. Russia’s attempt to impose an effective blockade on the Black Sea, even in the utmost appeasement textbooks, should qualify as an attack on a member state if free and unrestricted maritime navigation in their “maritime areas” is imperiled. If the benchmark is Russia’s MoD jargon, then vessels potentially destined to Ukraine, and naval blockades such as the current one, are interpreted by Moscow as acts of war, and Black Sea countries, should reasonably expect NATO protection guarantees to be enforced. Russia is now exploiting this weak spot in NATO’s defense shield.

What has Russia said with its current actions?

Russia’s current actions show that it is prepared to use its naval power to coerce Ukraine and its allies. Russia also says it is unafraid to challenge NATO, even if it risks a wider conflict. This adds to the same adage – if a loss in the Ukrainian war is inevitable, Mr Putin had better lose to NATO, not to Ukraine.

The endgame for the Kremlin in the grain deal and the naval blockade of Ukraine is a double win – higher grain prices and devastating the grain export potential of Ukraine. Concurrently, Moscow would project its food weapon on a global scale and generate frictions between Ukraine and neighboring East European countries, used for alternative and more expensive land routes for Ukrainian grain exports. Millions of people worldwide are facing food insecurity, and the situation is likely to worsen if the blockade continues. The Kremlin’s is counting on weaponizing food, in the way it has previously use energy exports, and starvation driven new migration that could flood the EU.

Mr Putin also delivers a message to Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey, that NATO security guarantees do not extend to the Black Sea and their security depends on bilateral arrangements with Russia. The Montreux Convention has loopholes, that the Kremlin exploits and the forthcoming NATO-Ukraine meeting needs to address both in the short and long term.

The immediate options are NATO warship reflagging to Black Sea countries, which seems the only NATO shared one, as all other solutions rests on Turkey’s Erdogan own power play with Putin. For whatever the trump cards the Turkish President holds in keeping the gateway to Russian naval and commercial traffic, all Black Sea countries will be greatly assisted by a NATO level naval and coastal defense assets reflagging program. Putin’s strategy counts on destroying most of Ukraine’s infrastructure and presenting the world with an irreversible fait accompli, on one hand, and on the other – on keeping Erdogan happy with lucrative deals – deferred payment and brokerage for Russian gas in the tens of billions of dollars.

Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Vershinin implied that Putin and Erdogan during their forthcoming meeting and phone calls will discuss control over maritime traffic in the Black Sea, which invites for a more pro-active role for NATO in designing and implementing countermeasures against Russia’s naval blockade of Ukraine and the Black Sea. Russia should not be able to rely on free access through the straits while it restricts the free passage rights of the ships of the other Black Sea states. The spirit of the Montreux Convention implies an analogous regime of navigation in the Black Sea and through the straits.

President Erdogan possesses trump cards to play in his standoff with Putin, with a range of counter play options, both short term and long term. One is the proposed Istanbul Canal, navigation through which would not be bound by Montreux Convention restrictions. Another is the possibility of blocking ships carrying Russian grain or crude oil through the Bosphorus (a right granted to Turkey under the Montreux Convention), as part of a NATO naval asset-reflagging operation.

In the context of this option, the Turkish president could consider a reduction of “carrot” – becoming less lenient about the transit of goods to and from Russia. Or he could go for more “stick” – by reviving the idea of a joint NATO naval force in the Black Sea or else having a NATO-backed Turkish naval escort operation for a grain corridor in the Black Sea. This could be pursued either through agreements between NATO and its members collectively, or else on a bilateral basis, if any member objects.

In a way, in fact, we’ve been here before.

Remember that it was Mr Borissov, not Mr Ergodan, that blocked the Joint NATO Black Sea Naval Force in 2016. And a sentence from a statement by the Turkish president in May delivered to a meeting of Balkan defence ministers in Istanbul – comes to mind: “We should turn the Black Sea back into a basin of stability through cooperation between the littoral states around the Black Sea” Moreover, NATO General Secretary Jens Stoltenberg had visited Turkey shortly beforehand, and Mr Erdogan reported telling the NATO visitor the following during his visit: “You are invisible in the Black Sea. Your invisibility in the Black Sea turns it into a Russian lake”.

This was all very promising, being a striking departure from Turkey’s traditional instinct for keeping non-littoral states out of the Black Sea as far as possible. But the promise was not fulfilled. A faction in Turkey’s military attempted a coup against Mr Erdogan in July of the same year. It failed, but the incident jolted the president into a new set of priorities: instead of Black Sea security, he became fixated on forging and consolidating a partnership with Mr Putin. Witness Turk Stream and the rest.

However, the underlying logic of Mr Erdogan’s words then remains valid now. And it’s not impossible that he may see fit to act on that logic, now that Mr Putin has proved such a troublesome and dangerous partner.

Let’s examine further the options beyond those involving restrictions on the Bosphorus. Turkey holds critical importance for Russia’s exports of natural gas, crude oil, refined products, and the transit of sanctioned goods to and from Russia. According to a report from the Atlantic Council, Turkey plays a vital role, as a NATO member, in supporting Russia’s economy, with trade volumes increasing by approximately 93% since the invasion. Especially notable is the fact that, between March 2022 to March 2023, Turkish electronic exports to Russia rose by a whopping 85%.

Vladimir Putin’s dependency on Turkey goes way beyond its status as Europe’s largest importer of Russian gas. So crucial was Turkey to the Kremlin that, when Mr Erdogan was facing re-election in May this year, Putin intervened heavily and expensively to help him win. This took the form of Gazprom agreeing to defer until end-2024 payment for tens of billions of dollars’ worth of gas delivered before May’s elections. And this was despite Gazprom’s desperate need for funds to support the Kremlin’s war effort. That is how much Mr Putin needs Turkey.

Moreover, President Erdogan’s role is vital for President Putin’s ability to transit gas to the EU via the “Turkish Gas Hub”, an idea that the EU and NATO are still considering seriously. At stake is over $30 billion in annual Russian gas sales and, more significantly, Gazprom’s ability to influence the EU gas market.

The dynamics between Putin and Erdogan involve high stakes and massive rewards, and should not be left solely to the discretion of the two men. NATO must play a prominent role in the matter and deny Russia its ambition to transform the Black Sea into its very own “internal lake”.

President Erdogan is now faced with a choice. He could opt for a greater role within NATO’s Black Sea defence initiatives. Or he could continue his strategy of playing the “middleman” between Russia and the West. But it’s doubtful whether he can do both at once – a least for much longer. Given the mayhem and emergencies that the Kremlin is creating in and around the Ukraine, that trick will become less and less feasible.

NATO, too, has a choice – though not very much of one. It must respond effectively to Mr Putin’s verbal aggression against Poland, and escalation in the Danube Delta and in the Black Sea, and it must do so very quickly. That can’t mean anything except engaging in damage-limitation and stopping the spread of the war. And if that means being nice to Mr Erdogan, then so be it. The alternatives are much less palatable.

Ilian Vassilev