The Vertical Gas Corridor and Russian Influence on Bulgarian Gas Policy

The second and third routes of the Vertical Gas Corridor—through the Greece-Bulgaria interconnector and the Alexandroupolis LNG terminal—are intended to expand transmission capacity to Romania, Moldova, and Ukraine. Their purpose is to diversify regional supplies by channeling non-Russian gas from Greek and Turkish terminals, along with future LNG imports. Yet progress has stalled, casting doubt on Bulgaria’s commitment to energy diversification. Although we have examined this issue before, the persistent delays in developing these two routes warrant a fresh review.

Stagnation in Infrastructure Development

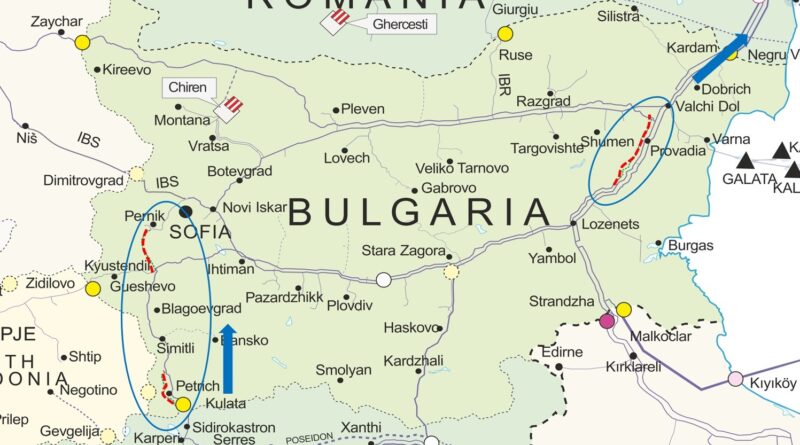

Despite a high-profile ceremony marking the launch of the first route and upgrades to the Sidirokastro–Kulata interconnection (see map), little progress has followed. The critical bottleneck—a missing 67 km pipeline between Rupcha and Vetrino, which could unlock an additional 13 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year of reverse flows through the Trans-Balkan Pipeline—remains unaddressed. Instead, Bulgartransgaz’s CEO has prioritized marginal expansions north of the Greek border.

Consequently, the Trans-Balkan system’s pipelines remain largely idle, while TurkStream maintains its dominance over regional gas flows. According to Bulgartransgaz’s website, the Kardam–Negru Voda 2 and 3 connections, with a combined capacity of over 13 bcm annually, show zero throughput. This represents Southeast Europe’s largest unused transmission capacity, capable of meeting demand in Moldova, Romania, and Ukraine.

In contrast, the older Kardam–Negru Voda 1 line, previously used for Gazprom deliveries to Bulgaria, now operates in reverse mode at near-full capacity. Daily “extra” gas flows have risen from 6 to nearly 15 million cubic meters (mcm), with nominations continuing to increase. This underscores the urgent need to activate the second and third Trans-Balkan pipelines, yet decisions are repeatedly delayed despite soaring seasonal demand.

Sources of Gas Flows

Although the Vertical Corridor is technically operational, only Route 1 (Sidirokastro–Kulata) delivers modest exports northward, insufficient to account for the ~15 mcm/day exiting Bulgaria toward Romania. A breakdown of entry flows into the Bulgarian gas transmission system reveals:

- Sidirokastro–Kulata (Greece): ~4 mcm/day, mostly backhaul – Russian gas – stable with no significant growth.

- IGB (Greece–Bulgaria Interconnector): ~2.5 mcm/day, fully absorbed by Bulgargaz’s Azeri contract.

- Strandzha (Turkey): ~4.5 mcm/day, primarily under SOCAR and Botas contracts.

- Strandzha 2 (TurkStream): ~50 mcm/day of Russian gas enters Bulgaria, with 26–28 mcm directed to Serbia and the remainder split among Greece, Bulgaria’s domestic market, Hungary, and Romania.

The data is clear: the bulk of increased flows to Romania and beyond stem almost entirely from Russian gas via TurkStream, not from Azeri supplies, American or other LNG from Greek and Turkish terminals.

Support Independent Analysis

Help us keep delivering free, unbiased, and in-depth insights by supporting our work. Your donation ensures we stay independent, transparent, and accessible to all. Join us in preserving thoughtful analysis—donate today!