Gas Delights in store

Part one

Slowly, discreetly, and on a small scale, the Turkish Gas Hub (TGH) is beginning to function, with Bulgaria’s transmission system operator Bulgartransgaz (BTG) playing a vital role in this scheme to bring Russian gas into Europe in the guise of “TGH mix”. Turkey and Azerbaijan are making full use of Russia’s break-off in relations with the West, caused by its ill-judged invasion of Ukraine, and of its lack of resources to deliver on its security guarantees in the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea. Meanwhile, the long-delayed project of expanding the capacity of BTG’s underground gas storage facility (UGS) at Chiren is finally poised to start. Ten years ago that would have been wonderful news and would have made perfect economic sense in terms of Bulgaria’s interest. But now, don’t fool yourself. BTG hasn’t finally seen the light. Chiren expansion is entirely geared to serving the needs of TGH.

History is repeating itself.

First there was the Turk Stream pipeline project, which, launched ceremonially in early 2020, was designed to take Russian gas under the Black Sea and across Turkey, crossing into Bulgaria and proceeding thence to Southeastern Europe (SEE) and beyond. This gave Moscow’s state-owned giant Gazprom the potential to circumvent those annoying Ukrainians in getting gas into Southern Europe. Skillfully steered past potential obstacles in Washington and Brussels – and officials who really ought to have known better – Turk Stream was in no small measure the achievement of Vladimir Malinov. He was (and is) the interestingly durable boss of Bulgarian transmission system operator (TSO) Bulgartransgaz – or BTG.

And now there’s Turk Stream’s upgrade, the Turkish Gas Hub (TGH). This too is a device for getting Russian gas into Southern Europe via Turkey, only after Russian president Vladimir Putin’s little indiscretion of invading Ukraine last year, some circumspection has been in order.

What’s going to be sold on the TGH is not “Russian gas”, but a “Turkish gas mix”, with gas from various sources blended in Turkey, so nobody has to feel bad about filling Mr Putin’s war-chest by buying gas from a company of which he is de facto CEO. Sure, there’s Russian gas in there, but there could also be Azeri gas, liquefied natural gas (LNG) from just about anywhere brought in via Turkish regasification (regas) terminals, and eventually maybe even some Iranian gas. In what proportions? Oh come on! Who’s bothered about details like that? Some Europeans certainly aren’t. And, quite possibly, Brussels isn’t either.

It’s Turk Stream all over again. History, as I said, is repeating itself. And if a very prolonged war in Ukraine eventually makes Brussels pickier, well, by then the scheme for “whitewashing” Russian gas by mixing it will be well-established and running smoothly. So it will be difficult for Brussels to do much about it. If India is whitewashing Russian oil, why should Turkey not launder Russian gas?

Indeed, in a small way, just a few weeks after BTG carried out its first (non-test) capacity tender for Turkish-Bulgarian gas flows at the Strandzha interconnection point (IP), the TGH seems to be up and running already.

These articles, analyses, and comments are made possible thanks to your empathy and contributions, which are the only guarantors of independence and objectivity in our work. The Alternatives and Analysis team.

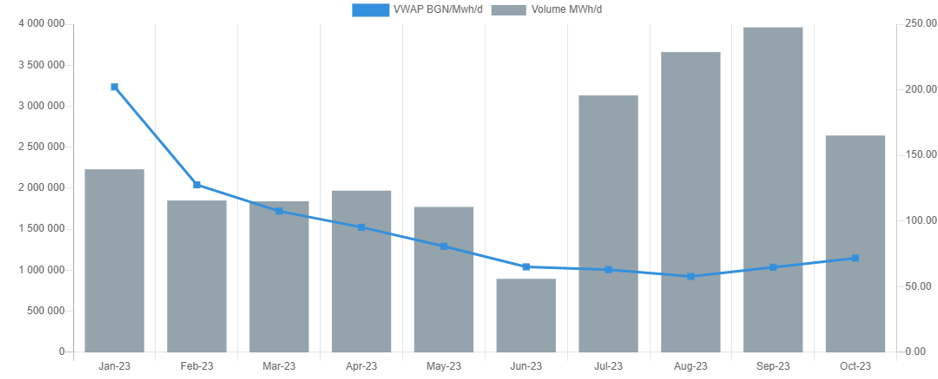

The caravan moves off

Last week Hungary announced a gas purchase from Turkey, while Romania followed, with Austrian-owned OMV-Petrom announcing, on September 27, a deal with Turkish national oil and gas company Botas involving the purchase of Turkish gas mix and the import of 4 million cubic metres per day (mcm/d) – up to 1.5 billion cubic metres per year (bcm/y) – via BTG’s transit system. Little Moldova followed suit on the very same day. And more imported gas from Turkey is being sold on the Bulgarian Gas Exchange – the Balkan Gas Hub – after entering from Turkey. A handful of companies are most active, the “usual suspects” for trade with Russian gas – notably WIEE, Sustainable Energy Supplies (owned by Litasco, LUKoil’s trading arm), and a few Greek and Turkish companies. The graph below confirms the substantial increase in daily trade volumes and the dynamics in the volume-weighted average daily price (VWAP) of gas traded on the Balkan Gas Exchange, operated by Bulgartransgaz.

Source: https://www.balkangashub.bg/

History is on the move, then, and it would be churlish to spoil the moment with trivia and quibbles.

Trivia like: how precisely is this making Bulgarian consumers happier, given that Gazprom has weaponised gas against Bulgaria, having cut off gas supplies to state-owned gas trader Bulgargaz in April 2022?

And quibbles like: isn’t it a bit ironic that the Russian gas giant has not merely cut Bulgargaz off, but is simultaneously profiting from the complete subservience of its sister BTG in readily transiting Russian gas and the (predominantly Russian) “Turkish gas mix” to Hungary and Romania? And to Serbia, of course, for recent news suggests that Serbia’s president Aleksandar Vucic has also caught the “import-gas-from-Turkey” fever…

No, let’s not yap and bark like dogs. For the TGH caravan is moving, gradually picking up speed. And doing so quietly and discreetly. No political hype came out of the summit-meeting between Mr Putin and his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdogan in early September. Nor has there been any hype since. Just quiet work on increasing gas volumes and clinching commercial deals – much as Alternatives and Analyses predicted at the time. And this isn’t a matter of good taste, but of good sense. Botas keeps exporting gas to the EU, and everyone halfway informed knows that it’s mostly Russian gas. But there’s no point in flaunting the fact, rubbing European noses in it. Especially as most Europeans would rather turn a blind eye anyway.

Three cheers for Chiren: expansion at last!

Alright, you might say, BTG and its eminence grise of a CEO are up to no good as far as TGH and whitewashing Russian gas are concerned. But surely they are doing something right in other respects?

What about Chiren? That’s BTG’s big underground gas storage facility (UGS) in north-western Bulgaria. Gas storage is very much in demand in Southeast Europe, so Chiren is a highly strategic asset. A very significant expansion of its storage capacity, from 550 mcm of gas to over 1 bcm – not much less than a doubling – has been on Bulgaria’s to-do list for more than a decade, but has not in practice been given much priority by BTG or its political masters.

But now it appears to be happening.

A contract for drilling of new wells and construction of surface infrastructure was signed in March 2023 and, last month, the expansion project was under discussion at a session of Bulgaria’s sector regulator – the Energy and Water Regulation Commission (EWRC) – which was dealing with BTG’s ten-year network development plan (covering the period up to 2034).

So isn’t that progress?

Well, it’s certainly a change. Let’s look at the background

A “bearded” project

The Chiren UGS expansion project has had EU “project of common interest” (PCI) status since 2013 and, unlike the Balkan Stream pipeline – the Bulgarian continuation of the controversial Turk Stream pipeline – has invariably been on PCI lists since then. The Chirenproject enjoys a similar status under the Three Seas Initiative (a forum incorporating the EU’s 13 most easterly members, with Ukraine as an observer). But for a decade, nothing happened. Not for nothing do energy experts call Chiren expansion the most “bearded” – that is, the most deferred – gas project in Bulgaria.

And, in economic terms, that deferment is just plain odd. If you compare BTG’s data on storage and transmission capacity utilisation in recent years, it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that, at any point in time, there would have been an overwhelming bankable case, in terms of demand, for expanding capacity at Chiren UGS, immediately and to the maximum degree possible. And that any operator taking decisions on purely commercial grounds would have carried out such an expansion ten years ago.

It was not just a question of Chiren, by the way. It was also a question of developing BTG’s system in a way that served the interests of Bulgarian consumers and the Bulgarian economy. Building interconnectors and expanding the internal gas transmission network in such a way that more consumers could enjoy natural gas would have been a good idea.

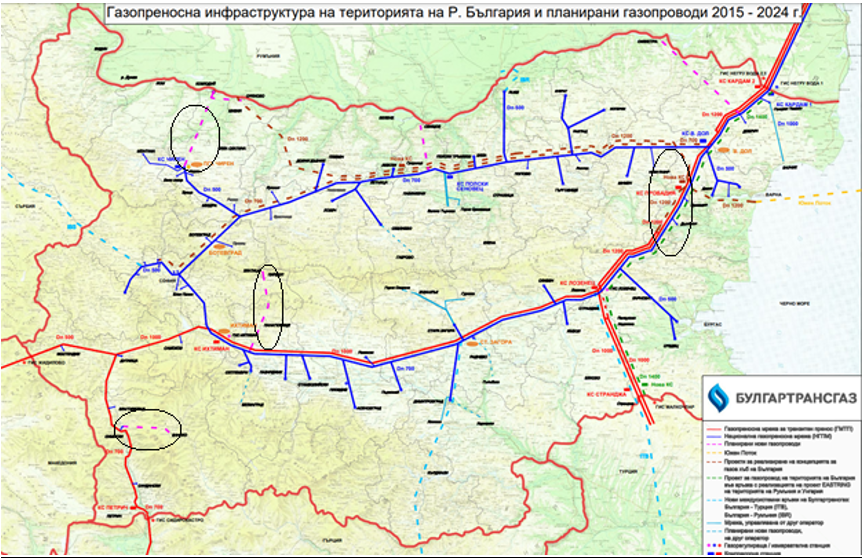

For instance, by building the offshoot pipelines that would have connected the important but outlying towns of Kozloduy, Bansko and Razlog to the main, ring-shaped gas transmission network as envisaged in BTG’s 2015 10-year Gas Transmission System Development Plan.

Source: Bulgartransgaz

Or by building the planned parallel gas pipeline between the Lozenets Compressor Station (CS) and the Nova Provadiya CS. That would have been handy, for it would have allowed the use, in reverse mode, of the Trans-Balkan Pipeline (TBP) to take gas received via Turkey to Romania and Ukraine. Given that the stretch of pipeline in question would only have been 60 km long, too, it would have been a pretty cost-effective investment. But again, nothing has been done – which may have something to do with the fact that the effect of not having said pipeline is that TBP is currently blocked by Russian gas and by Turk Stream.

But expanding Chiren was logically pretty central. Done in a timely fashion and done properly, it would have enabled Bulgargaz – and anyone else in the region – to store cheap gas in the summer to balance winter consumption. Really it was a no-brainer.

But BTG’s management had other priorities. It systematically ignored both Chiren expansion and the other “Bulgarian-oriented” agenda items in the name of implementing the Turk-Balkan Stream project, which specifically served Gazprom and its partners.

Now, if pressed, Mr Malinov and Boyko Borissov, the long-serving prime minister who presided over his efforts in putting Turk-Balkan Stream in place, argued – and still argue – that ultimately Bulgaria gained, as Turk Stream expanded its potential to transit non-Russian gas and serve Gazprom’s competitors. Well, “ultimately” and “potential” are slippery terms. Serving Gazprom is the sum of what Turk Stream does now, of what it’s likely to do in the foreseeable future, and of what it was really ever likely to do. The rest is virtual future reality with no net present value.

Chiren UGS: at your service, Mr Putin!

We digress, however. Regardless of history, can’t we agree at least that it’s good news that the Chiren expansion is finally on the agenda?

Far from it. In fact, if you think the Chiren UGS expansion project, as at present conceived, is aimed at anything other than serving Russian gas interests, you are dead wrong.

Think about it. Transporting large quantities of natural gas from Turkey boils down to hiring the necessary entry and exit capacities, and hitting the optimal mix of long-term and short-term products (monthly, quarterly, annual, and multi-year). The TGH team has pretty much cracked the former problem. And the latter problem is technical and commercial, hardly beyond the wit of such a talented bunch.

But the next most crucial element in this equation is the availability of gas storage capacity large enough in volume – and flexible enough in access – to allow response to market fluctuations and ensure sustainable gas flows. That’s what Chiren UGS will do for TGH (and thus for Messrs Erdogan and Putin). And it’s not obvious it will be doing very much for anyone else.

Witness some rather pertinent – or, if you work for BTG, impertinent – questions asked by EWRC – Bulgaria’s regulator – chairman Ivan Ivanov at the public hearing, dedicated to the new 10-year Plan for Development of the Gas Transmission System. The answers to these made it clear that, after the expansion of the Chiren UGS, there will be a second UGS entry-exit point at nearby Butan, which will be connected only to the Balkan-Turk Stream – that is, to a pipeline through which only Russian natural gas flows. In other words, only companies that trade and transport Russian gas from Turkey via Turk Stream – Botas, Gazexport, Socar Enerji, MET, MVM, etc. – will be able to make direct use of the expansion of the Chiren UGS and the new facilities associated with it. And there ends the ‘common’ EU interest in the project.

Balkan Stream: for everyone – in principle…

Pressed by the EWRC chairman, the representatives of BTG muttered that, in principle, anyone could use Balkan Stream and store gas in the expanded UGS through the new entry point of Butan. When asked how many Bulgarian companies, not in principle but in reality, use the “free” capacities of Balkan Stream, the answer was laconic: “none”. That was not an accidental gaffe. It was the literal truth – reflecting decades of deliberate discrimination against Gazprom’s competitors.

In theory Gazprom does not control 100% of the transit capacity of Balkan Stream – entry to which is at the Strandja IP on the Turkish border and exit at Kireevo on the Serbian border. In practice, however, it does control 100%, since anyone else would need to secure two things in order to perform such a transit:

-

- First, they would need to secure both ownership of gas in, and exit capacity from, Turkey.

-

- Second, they would need to secure entry capacity into Serbia.

And, in practice, neither of these things is possible – except for those whom Botas and Gazprom (or one of its closest friends) really like.

Turkish vs Greek Gas Hub

Since the beginning of September, gas flows from Turkey have reached new peaks, reaching record levels of almost 50 mcm/d for combined entry capacities at Strandzha and Strandzha-2. In the interim, gas flows from Greece have fallen to just 2.8 mcm/d, down from highs of 6.3 mcm/d earlier in the 2023. And the LNG schedules for October at the Revithoussa regas terminal in Greece tell a similar story. There are, in fact, just two such schedules – one for Elpedison and one for Mytilineos. Interesting enough Mytileneos buys at TTF minus its LNG cargo, sells at TTF plus price to Bulgargaz, and in the interim Bulgargaz slots at Revithoussa for October cargoes have vanished!? Which confirms that there has been a decisive shift in the preferences of Bulgargaz and Bulgartransgaz: they want to serve clients from Turkey far more than those from Greece.

David challenges several Goliaths

Bulgaria’s Parliament has unexpectedly produced a potential bombshell by adopting amendments, effectively introducing a BGN 20 (€10.2) per MWh energy tax on the import and transit of Russian gas. The repercussions could be potentially immense, as at current TTF price levels of €33/MWh, the tax will effectively kill the competitiveness of Gazprom in favour of LNG and non-Russian gas.

The fallout from this move remains to be see, but we can confidently expect cries of “foul” both from Mr Vucic and from Hungary’s strongman-prime minister Viktor Orban – who, incidentally, is planning a nice little Central European hub of his own, based on TGH gas, that will rival or even displace Austria as a regional gas hub. We can assume that Bulgarian President Rumen Radev won’t be too pleased either. And nor will Mr Putin: at current levels of imports of Russian gas, the move will knock €2 billion per year off Gazprom’s balance books, too deep a dent for Mr Putin’s ego. So that should mean an interesting time politically in Bulgaria in October and November. Expect turmoil – and maybe non-confidence votes, protests, and a coup attempt or two.

Whatever Mr Putin feels about it, however, Mr Erdogan could, in an odd way, actually profit from the situation. The freshly imposed energy tax may effectively leave Gazprom with no option but to whitewash its gas in Turkey and export it as a “Turkish Gas Hub mix”.

And then there’s Brussels…

Apart from all that, there’s the question of US and EC attitudes and reactions. That’s partly a matter of dealing with business and projects in which Gazprom is involved; partly a matter of ensuring that the likes of BTG are held accountable, stick to the rules; and partly a matter of interpreting those rules and determining how strictly and literally they are to be enforced.

That’s a big subject, but suffice it to say here that the EC has recently been somewhat muted in public and more than somewhat conflicted. Torn, that is, between, on the one hand, taking seriously its own political declarations of willingness to cut dependence on Russian natural gas and limit flows of cash into Mr Putin’s war chest; and, on the other, its instinctive laissez-passer leniency towards the Trojan horses of Russian gas in the EU.

Ilian Vassilev