The Solidarity Ring project: Part 1

Turk Stream upgraded: Same people, same goals

This week’s gathering of the region’s energy notables in Sofia will advertise and celebrate the inauguration of the Turkish Gas Hub – newly rebranded as the “Solidarity Ring” project (or, somewhat uncharismatically, “String”). The meeting will sing its praises as marking the debut of gas from Azerbaijan on the Central and East European (CEE) market. That’s only a rather small part of the truth. As we show in Part 1 of a two-part article, what’s mostly going on is in fact an audacious operation on a grand scale to sneak gas from Russia’s Gazprom into CEE by a backdoor route now the “front door” has been closed as a result of Vladimir Putin’s brutal invasion of Ukraine

The Turkish Gas Hub (TGH) is a project conceived by the Kremlin and implemented by the Turkish government. It is a reaction to two facts.

- First, that what has for more than a decade been the main route for Russian gas to Europe – the Nord Stream pipeline to Germany – is now defunct, and quite likely to remain so.

- Second, that Russian gas will for some time be unwelcome in Europe, at least to the extent that advertising itself as Russian will not be very prudent.

This being so, there was a need for a device to provide an alternative, southern route to transport as much as possible of the Russian gas that would previously have gone west via Nord Stream – and to avoid making it look “too Russian”. A secondary aim of the project (at least from the Kremlin’s point of view) is to increase Turkey’s gas liquidity by significantly raising its capacity to import, store, and distribute natural gas from various sources, including Turkey’s own gas production, as well as Russia, Iran, and Azerbaijan – and also LNG.

That’s nice for Turkey, enhancing its revenue, strategic positioning, and access to gas. It’s also nice for Russia, because it makes it easier to fudge the question of origin: it’s more difficult to identify gas as specifically Russian rather than as part of a general “Turkish mix”. It is also nice for the cohort of politicians and String facilitators that will reap personal gains from linking the TGH Russian mix to Central and Eastern Europe.

So the potential is for a Russian gas ‘invasion’, circumventing sanctions and allowing Russian leader Vladimir Putin to replenish his war-chest with the proceeds of renewed gas sales. As Alternatives and Analyses (A&A) has demonstrated several times over recent months, events have already given support to this conclusion. And forthcoming events are about to give it even more credibility.

The Solidarity Ring (String) Project

One event should top the watchlist – the forthcoming high-level meeting scheduled for April 25 in Sofia, bringing together leaders and energy ministers from Azerbaijan, Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Slovakia. It will launch the new project, the “Solidarity Ring” (String) route and the integrated infrastructure which is ostensibly for exporting Azeri gas to CEE.

In fact, however, it is much more about blocking the reverse flow via the Trans-Balkan pipeline for gas leaving Turkey; about trade in whitewashed Russian (more than Azeri) gas; and, most importantly, about bypassing Ukraine – for, just before entering Ukraine, the String route makes a sharp detour to the West and Hungary. It is hardly a coincidence that the main proponents of the String project – besides Mr Putin and Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan – are Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orban and Bulgarian President Rumen Radev, both known for their pro-Russian sympathies. The event’s hidden agenda rotates around the TGH’s launch, which will clear the transit route to the end-recipient countries.

Why does Russian and not Azeri gas take centre stage?

Azerbaijan’s key player, the State Oil Company of the Republic of Azerbaijan – or SOCAR – has repeatedly stated its limitations in exporting additional gas volumes before 2025, when initial production in the Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli (ACG) Deepwater and Absheron (1st phase) fields will come online. For the record, the gas from Azerbaijan’s main oil field, Shah Deniz II, is entirely contracted by the consortium’s gas trader – the Azerbaijan Gas Supply Company (AGSC) – for export to Italy (via a route which comprises the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline [TANAP] and the Trans Adriatic Pipeline [TAP]). Therefore, SOCAR’s own additional gas export potential – consisting of non-Shah Deniz 2 gas – is much more limited. Many South-East European (SEE) leaders, landing in Baku and pleading for emergency gas supplies, have consistently received this message: “not before 2025 – and you will need to clear the Turkish transit issue with President Erdogan.” And yet, relatively small additional volumes of Azeri gas have emerged, although they are still dwarfed by the volume of Gazprom gas – almost 60 bcm of it – that is now ”orphaned” and desperately looking for a backdoor entry to the EU market.

Azeri gas – the perfect smokescreen

Bulgartransgaz (BTG) – which operates the Bulgarian gas transit system, as well as being the country’s transmission system operator (TSO) – has promoted the Sofia April 25 event, which will be hosted by the country’s President Rumen Radev, as the grand opening for Azeri gas entry into Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and for a new route by which 16-18 bcm can enter the CEE market. Hence the pitch to the European Commission (EC) that it is a breakthrough for diversification of the region’s supply away from Russian gas.

A closer look at details, however, leads to precisely the opposite conclusion: that this is another attempt to secure desperately needed alternative sales and revenues for Mr Putin by using Azeri gas as a disguise for Russian gas laundered via the TGH.

Some history

In 2021, Shah Deniz II gas started flowing via TANAP-TAP and a piped alternative to Gazprom gas supplies finally became available to one country in the CEE – Bulgaria with the promise to reach many more. These projects had been preceded by the Nabucco-vs-South Stream rivalry, which took centre stage after 2002. In both instances, Russia has been hard at work. It’s been using all its political, economic, and financial leverage to divert competing, mostly Azeri, gas supplies away from Ukraine and CEE. And, so far, it has succeeded. The Nabucco project was dumped in 2012, while the TAP, the choice of the Shah Deniz II consortium, diverted Azeri gas away from the CEE region to Italy. Bulgaria has, in fact, been the only CEE country to receive Shah Deniz II gas since 2021 under a 1 bcm/y contract signed in 2013. But even in that case Gazprom managed to minimise the diversification effect by ‘incentivising” the right people to block and delay the completion of the interconnector Greece-Bulgaria and later to buy less Azeri gas, than contracted. These “right people” were Bulgaria’s top politicians and sectoral managers – those of the national gas trader Bulgargaz and Bulgartransgaz, the TSO. They adopted a wartime (“at all cost”) mobilisation effort to complete the Turk Stream pipeline in time to allow Gazprom to retain its dominant role over the regional market by means of long-term supply contracts.

And the upshot was that Azeri imports were discouraged to the extent that less than one-third of the volume contracted Bulgargaz – a meagre 300 mcm/y – was actually taken up by Bulgaria. It was only in July 2022 that full contracted volumes of Azeri gas started entering Bulgaria, thanks to the reformist and pro-Western government of Kiril Petkov – which was duly toppled soon afterwards. That plunged the country into a still-unresolved political crisis overseen by interim governments appointed by President Radev. Russia’s interests played, and still play, a major role in this crisis.

The String Project – one more ‘pincer’ around Ukraine?

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine was preceded by systematic preparatory work designed to dry up alternative gas supplies to Ukraine while executing a ‘pincer’ strategy – the pincers in question being the Nord Stream and Turk Stream pipelines. However, shortly after the Russian army entered Ukraine in February 2022, Nord Stream ceased to be ‘the route’ to Northern Europe, while EU countries stopped buying Russian piped gas and LNG – which left some 60 bcm of Gazprom gas without customers and caused a drop in energy revenues at a critical time for Mr Putin’s war in Ukraine. So the Kremlin started immediately looking for alternative options for sales and deliveries to the EU.

But while deliveries via Gazprom’s Northern route ground to a halt – and Nord Stream-2, expected to start operating, failed to do so – the Southern route, the Turk Stream pipeline, was a complete success. This made Mr Putin believe that an encore and an upgrade were possible, expanding Gazprom’s reach to the North by using the now-redundant Trans-Balkan Pipeline (TBP) in reverse-flow mode, carrying gas northwards and westwards along the route that had once supplied SEE and Turkey, diverting gas and revenues away from Ukraine and its massive storage facilities.

The Kremlin trusts it can pull the same levers it used during the Turk Stream saga, presenting its over-lenient adversaries, the EU and the US with another fait accompli. Moscow now considers the “success story” of Azeri gas – once seen as a deadly threat – to be a potential life-saver, using it to conceal a “laundering” operation involving a significantly larger volume of Russian gas via the Turkish Gas Hub (TGH). This will also feature a TGH gas price benchmark which, the Kremlin’s “String Theorists” hope, will become the Europe’s premier gas price, displacing the current EU benchmark, the TTF – which reflects pricing on a Netherlands-based regional exchange. It’s an essential part of the Kremlin playbook to undermine NATO and the EU, joining the dots of vulnerability in the CEE region from Hungary to Turkey – Erdogan-Radev-Orban.

The Supply Side

Russian LNG sales increased throughout 2022, adding more than $14 billion to Russia’s gas revenues. That, it seems, is continuing this year: the heavyweight sector information provider Energy Intelligence says that, in the first quarter of 2023, Turkey was the leading destination for Russian LNG cargoes leaving Gazprom’s recently launched Portovaya LNG facility on the Baltic Sea coast – which would seem to reflect the difficulty of marketing Russian LNG elsewhere in Europe due to sanctions.

Russian gas enters Turkey via Blue Stream, Turk Stream 1 and 2, and LNG. The surplus supply – the difference between imports and local consumption – is most notable on the LNG side, but will be also helped by the start of gas production in Turkey’s Black Sea Sakariya field (the 10 mcm/d announced by Botas). Under President Erdogan, Turkey has refused to join EU sanctions, instead opting to benefit from the abundance of gas that Gazprom can no longer sell via Nord Stream by brokering its sale to the EU via the TGH. Russian LNG tankers have regularly docked at Turkey’s Marmara Ereglisi regasification (regas) terminal near Istanbul, boosting the buffer stocks of excess gas that EU companies can buy in Turkey for re-export.

Political risks

Mr Erdogan faces presidential elections next month and sees TGH as a key factor in his electoral success. He needs Mr Putin and his CEE partners to play up the gas theme in the campaign. And beyond the elections? Well, Mr Erdogan is in practice unlikely to lose his grip on power, he has invested too much in his autocracy to lose. So we can assume that he will be there, acting as broker of Mr Putin’s gas to the EU, for some time to come.

Less comfortable is the position of Azerbaijan and its president Ilhan Aliev. He is stuck with total dependence on Turkey for the transit of its oil and gas. Moreover, the credibility of Mr Erdogan’s TGH project depends on maximum gas liquidity and imports of Azeri gas – and occasionally of US and European LNG as a geopolitical and PR counterweight. Only in this way can Turkey maximise its benefits in the lucrative role of exporter of a “TGH gas mix”: indeed, only this way can the very notion of such a de-russified mix seem plausible. This means that it is likely that the Turkish state gas company Botas will henceforth discourage the use of direct transit for future flows of Azeri (or any other) gas – one of the real reasons why, to this date, there is no intersystem agreement between the Turkish and Bulgarian TSOs.

Mr Aliev can ill afford to disengage from Mr Erdogan’s gas interplay with Mr Putin. So, the Azeri head of state will arrive in Sofia, having agreed to inaugurate a SOCAR office in Sofia, attend the high-level gas meeting and play his part in the String-TGH’s promotion.

Not that he hasn’t tried to help SOCAR sell its gas directly to EU customers, bypassing Mr Erdogan’s hub:

- At the end of 2022 and the beginning of 2023, for example, SOCAR supplied some modest gas volumes to Moldova, via the IGB, which triggered alarms in Moscow.

- State-owned Romanian national gas company Romgaz bought 0.3 bcm from SOCAR this winter. Promises and more sale contracts followed – including a one-year contract with Romgaz for 1 bcm, starting on April 1, 2023.

- Then Hungarian deputy premier and energy minister Péter Szijjártó signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for the supply of 2 bcm of SOCAR gas – while also confirming the extension of the significantly larger Gazprom supply contracts via Turk Stream.

- Finally, Serbia’s mining and energy minister, Dubravka Djedovic, recently said that there was a possibility of a long-term Azeri gas supply contract covering one-third of the country’s needs – i.e. roughly 0.85 bcm/y.

So the narrative that the grand entrance of Azeri gas onto the CEE stage is the underlying reason for the String project (and the Sofia meeting) seems at least partially credible. However, the distinction between declarations and reality is much more blurred than this “big picture” take would suggest.

To begin with, let’s note the stark difference between the potential volumes of Azeri gas (<3bcm/y), that make the headlines and Russian gas (>40bcm/y), that, according to the Turkish officials, will be traded at the TGH, on one side, and the total capacity of the Trans-Balkan Pipeline (TBP) (20 bcm/y), the main exit route for the TGH mix. To be precise, the CEO of BTG and the main driver behind the String project, stick to referring to “16-18 bcm/y” reverse capacity in the TBP, which will involve a 4,7 bcm/y reverse capacity increase between CS Kardam and CS Negru Voda 1 and 2. Note that when reference is made to the TBP second line, the String project includes the capacity of the third line as incorporating the TBP transit lines.

The routes

Most Azeri gas supplies have so far relied, for access to TAP, on using the recently-commissioned Greece-Bulgaria Interconnector (IGB) and Bulgaria’s transit system. Until, that is, the beginning of April this year, when the Strandja-1 entry point between Turkey and Bulgaria restarted operation and the BTG started promoting this entry point as the gateway to the EU of Azeri gas.

The first time this ‘dormant’ entry point attracted experts’ attention was in December 2022, when Botas and Bulgargaz signed an agreement, nominally granting the Bulgarian trader access to Turkish LNG terminals. However, the deal remained a commercial and state secret after the government approved it, and few details emerged. Even fewer questions were answered by either the managers of Bulgargaz or Bulgarian energy minister Rossen Hristov on the nature of the deal – and more specifically on questions of its lack of transparency and intersystem agreement, of equal treatment for other EU companies, and of compliance with EU regulation.

Apart from that, there was the question of insufficient guidance provided by BTG to companies wishing to use and book entry capacity at Strandja-1, given the fact that the absence of an intersystem agreement with Turkey made it impossible to secure exit capacity from the Botas-operated Turkish transmission system. The EC was clearly at fault in failing to intervene too, as the exclusive deal of Bulgargaz with Botas was an obvious breach of both EU energy regulations and EU anti-trust legislation.

Strandja-1 entry point – reactivated

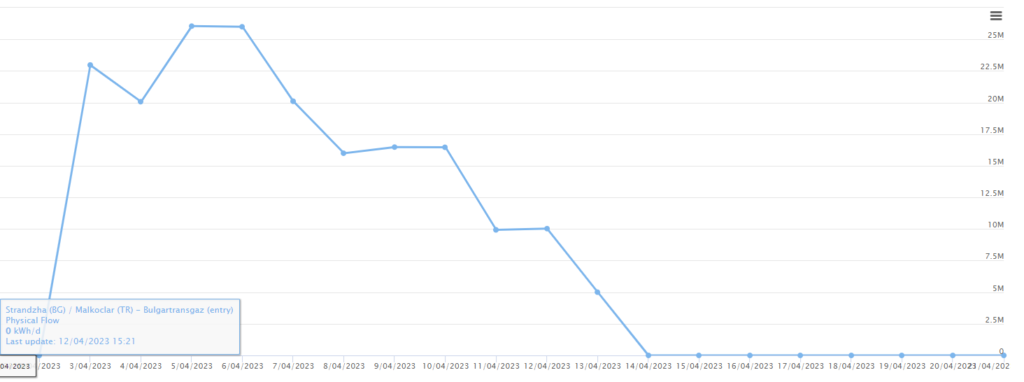

Data from ENTSOG – the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas – suggests that the Malcoclar-Strandja-1 interconnection was activated on April 2, when gas started flowing from the Botas system into Bulgaria. By the time of this article’s publication, gas volumes were in the range of 5-23 mcm/day. Final flows were registered on April 14, which implies a testing mode operation.

The restart of the Marcoclar-Strandja 1 IP – marked by the delivery of the first 55 mcm of LNG-derived gas to Bulgargaz via the interconnector – was given a very definite spin by Bloomberg, in an article headlined “Turkey opens gas link with Bulgaria to blunt Russian dominance”. However, Bulgargaz announced on April 12 that its first tanker of LNG under the Botas contract had docked at the Marmara Eriglisi terminal, loaded with US Cheniere gas. The ENTSOG data above clearly indicates that gas entering Bulgaria before that date had certainly not been US LNG and was more likely Russian LNG that had arrived earlier.

Further data checks show that, in the first ten days of April, gas flows via the Kardam-Negru Voda IP (between Romania and Bulgaria) increased commensurately, which coincided with announcements made by Romgaz on the start of Azeri gas supplies. But then, Azeri gas was supposed to enter Bulgaria via the TANAP, and thereafter the TAP-IGB route, as the Strandja-1 entry point, given the absence of an intersystem agreement and capacity allocation procedure by BTG, was confined to short-term capacity allocation. Yet, judging from ENTSOG data, there is no trace of any increased gas flow via the IGB during that period.

Furthermore, BTG’s plans strangely omit the fate of the long-term transit contract between itself and Gazprom Export (GPE) for the capacity of lines 2 and 3 of the TBP, which seems has been incorporated in the Turk-Balkan Stream transit service contract. It has been an ‘expert community’ secret that, at least until the completion of the Turk Stream pipeline, Gazexport had continued to pay for capacity booking of those two lines of TBP under a ‘ship-or-pay” clause (involving 70% of the due sum). Meanwhile, it is worth reminding ourselves that Gazexport (GPE) has prepaid transit fees to BTG until the end of 2023. It also seems plausible that BTG could auction the Strandja-1 and Strandja-2 entry capacity – a combined total of 60 mcm/d – jointly, which could again help blur the difference between gas originating via Turk Stream-2 (100 % Gazprom gas) and the TGH (gas mix).

Turkey vs Greece or Russia vs the EU?

The reactivation of Strandja-1 and the volumes implied for transit from Turkey directly impact gas flows from Greece, since they are competing for the same transmission infrastructure.

Greece has plans to build up its capacity to import LNG and other gas to 30 bcm, which (given that Greece itself only consumes around 5 bcm/y) leaves more than 25 bcm for export, mostly via Bulgaria. Turkey’s plans top 45 bcm for potential export too, mostly again via Bulgaria. The recent market test for additional capacity booking in TAP has generated only moderate interest, amounting to just 1.2 bcm/y – 1 bcm/y more for Italy and 0.2 bcm/y for Albania. Which implies that the potential for additional gas imports is mostly in a northbound rather than a westbound direction – i.e. that they would flow via Bulgaria to CEE.

When comparing plans for dedicated entry and exit capacity allocation from Greece via the IGB and from Turkey (the String project) via the Strandja-1 and -2 entry points, it is easy to discern that Bulgartransgaz is eager to prioritise natural gas flows from Turkey over those from Greece, and engage in direct transactions for Azeri-Russian-TGH mix gas via Turkey. Ostensibly, that makes economic sense in terms of potential cost savings. But two questions in particular arise:

- Whether the TGH option is in fact a cheaper choice of route. Energy minister Hristov recently denied that it is cheaper to import LNG via Turkish than via Greek terminals. It is also highly questionable whether Russian gas mixed in Turkey will be cheaper for Bulgarian customers. Doubts hung in the air, as regulated gas prices in Bulgaria – which incorporate route-cost differences that, according to minister Hristov, are in any case negligible – continue in April to exceed Dutch gas hub benchmark (TTF) prices by a substantial (10%) margin. Given that Azeri gas imports are the cheapest in the EU and that its recent take-up by Bulgargaz is at 100% of contracted volumes, the fact that regulated prices are well above TTF levels can have only one explanation. Namely, that the Bulgargaz buy price for gas delivered at the Bulgarian border is well above TTF at a time of gas oversupply and sinking prices, hence higher-than-usual discounts to the TTF benchmark. This in turn means that intermediaries (and potentially corruption) are involved and that Russian gas is being bought at record high prices – which is an indirect war subsidy to Mr Putin.

- Whether the gas that enters Bulgaria via Strandja-1 is in fact Azeri – or whether it is a differently sourced gas mix at the TGH, which primarily serves to disguise larger Russian LNG imports. Suffice it to compare the times of the discharges of the earlier – April 10th Russian and April 12th US Cheniere – tankers at Marmara Ereglisi and the data on flows via Strandja-1. The whole String project favouring TGH gas-mix imports into Bulgaria should trigger a closer look not only at direct sanctions on Russian gas, but also at sanctions that deny Russian gas access to EU gas infrastructure – terminals, storage and transmission lines. As presented, this is more a sanctions circumvention project than an instance of sanctions compliance.

However, the TGH faces challenges that appear difficult to resolve, despite the geopolitical levers that are being pulled by Russia and Turkey; despite those two powers’ unrivalled experience (and conspicuous success) in taming EU and US opposition in the case of Turk Stream; and despite the behind-the-scenes political manoeuvres of Mr Putin’s agents in Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary and elsewhere in the region.

The fact is that several things have changed:

- The political scenes of the EU and the US are looking rather different, no longer being dominated by former German chancellor Angela Merkel and former US president Donald Trump. The Turk Stream was made possible by a Putin-Mohammed bin Salman-Trump transactional diplomacy, that is off the cards at the moment.

- No doubt the Bulgargransgaz CEO – Lord of the String Vladimir Malinov – will again opt for a give-and-take, transactional approach. He will try to repeat an operation involving imports of US gas turbines for pipeline capacity expansion, while leaving to their US producers to lobbying the deal through the State Department. Occasional deliveries of US LNG will also fit into this scenario. But it is unlikely that, given the direct causal impact of such a TGH-String deal on Mr Putin’s war chest, both the EU and the US will again turn a blind eye this time. There’s a war on, and the EU and NATO have expressed resolve to use sanctions against Russia’s energy weapons – which makes the sort of transactional energy diplomacy that delivered Turk Stream seem out of place now.

- Finally, Mr Putin has been indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Court, which makes indulging in geopolitical plays with him a questionable and – since potentially criminal – even dangerous activity. And that’s how it must seem even to the likes of Hungary’s Viktor Orban and the Bulgarian tandem of Messrs Radev and Borissov – even accustomed as they are to dealing with the cynicism of the Kremlin.

Ilian Vassilev