Vladimir goes global – Part 2

With friends like these….

Now some readers of Analyses and Alternatives (A&A) – especially those who read it only occasionally in order to raise their blood pressure – may say: “There goes Vassilev again, talking up the Apocalypse and tracing all evil to the man in the Kremlin. Prove it, ambassador!”

Well, anything approaching forensic proof is the province of intelligence agencies now – and of historians (and maybe international tribunals) in future – and not of mere members of the commentariat reliant on open-source materials. For us mortals, it’s sometimes necessary to form judgements as best we can now – while something can still be done about the situation – on the basis of available evidence (even if it’s circumstantial), reasonable presumption, and probability.

And a lot can be done by two means:

- First, by using the old Roman legal maxim of “cui bono?” “Who benefits?” If you want an idea of who might be guilty of a crime, it helps to ask who benefits from it. Or perhaps, to ask who expects to benefit from it.

- Second, by observing who went where and when. In this case, it can be very instructive to see which capitals Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov and his deputies visited, whom they are reported to have met at international gatherings, and who came to see them in Moscow. And, sometimes, by reading between the lines of the bland official reports of such visits and encounters – or drawing inferences from the seniority of those involved.

Candour with Carlson?

Though there is also, of course, self-incrimination. And Mr Putin has managed a fair amount of that lately. Specifically, his recent marathon interview with US talk-show host Tucker Carlson – sacked last year by Fox News – could serve as compelling evidence at the International Criminal Court, providing proof positive of the Russian leader’s geopolitical Luddism and ambition to reshape (or retro-shape) the world in pursuit of Russia’s glory and his own historical legacy. Used to hearing, relaying and purveying so much falsehood, Mr Carlson – visibly overwhelmed by Mr Putin’s fanciful half-hour history lecture at the beginning of the interview – must also have been taken aback by his frank avowal of motives and ambitions.

While there may be disagreement over the details, the undeniable reality is that the Russian president’s intention, as articulated in the interview, is to triumph in the war and undermine the West. This intention is reinforced by the extensive subversive global network at his disposal – coupled with the notable absence of moral constraints that is evident in his historical justification of Hitler’s invasion of Poland and the Fuehrer’s pact with Stalin.

Mr Putin operates without domestic institutional or legal checks and counterweights, having dismantled the last vestiges of democratic rule and wielding absolute power. His relentless obsession with subduing Ukraine, NATO and the EU is there for all to see, and driven by a deep psychological impulse.

There is a discernible Russian footprint in almost every active hotspot on the global conflict map – whether the Kremlin is proceeding through direct interference or pre-emptive action to prevent conflict resolution.

Moreover, Mr Putin has brought his revived messianic ambitions to bear on his old goal of influencing US politics, mirroring his involvement in the 2016 presidential elections. With one difference. Eight years ago it was Mr Putin’s intelligence services that were tasked with undermining US democracy. Today the man in the Kremlin himself is personally engaged in the race for the White House, openly supporting a particular candidate – courtesy of the obliging Mr Carlson.

Unintended consequences

Despite Mr Putin’s self-image as Grand Strategist, however, his tactical decisions often have unintended consequences that are anything but “grand” from his point of view.

The new Tsar assumes that he can maintain control over his network of ostensible allies around the world – from North Korea, Iran and China to India, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Turkey – and that he can ensure that they obligingly meet his current arms and cash needs.

But, in fact, recent setbacks remind us that this isn’t the case.

One such, news of which broke just a few days ago, involves the Zhejiang Chouzhou Commercial Bank (CZCB). This is a major Chinese bank, of systemic importance at home and a key channel for Russian importers. And it has “temporarily” stopped working with Russia and Russian vassal state Belarus. This is causing problems of business logistics, leading to closure of accounts, disruption of payments and delays exports, especially since the decision coincided with the upcoming Chinese New Year holiday.

The Chinese authorities referred to US sanctions as the main reason, but the choice of timing surely added a grain of suspicion as to the real motives. It remains unclear so far precisely what the real meaning of the CZCB decision is. But it’s an unwelcome complication for trade – and if similar restrictions affect other Chinese banks, things could become more complicated still. And, so far, things don’t look good for Mr Putin. Reportedly he has talked to his friend Mr Xi about the CZCB issue. But without visible result so far.

Another setback concerns the wily Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose balancing act between East and West has long been a source of both joy and frustration to the man in the Kremlin. The latest twist in the tale is that Mr Erdogan has outmanoeuvred Mr Putin in tactical negotiations over the Turkish Gas Hub and the idea of selling Russian gas to the EU, leading to the last-minute cancellation of the Russian president’s trip to Turkey.

We’ll deal in the next part of this article with Mr Putin’s conspicuous lack of Turkish Delight. Meanwhile, it’s a reminder that the Russian leader’s career prospects as global wrecker and profiteer from worldwide havoc are by no means unclouded. A more nuanced and sober approach is in order.

In fact, let’s take a brief A&A Asian Tour, to determine whether Mr Putin’s relations with his key allies are in geopolitical surplus – or geopolitical deficit.

The view from Tehran

Let’s start with what (Belarus aside) is presumably Russia’s closest ally – namely, Iran. Even in this case, the situation is less clear cut than it seems.

The Moscow-Tehran alliance is obviously very active – increasingly so – and for many purposes the two states’ interests are almost identical.

The dominant interests within Iran’s elite are a mixture of two groups:

- First, a collection of clerics who are socially conservative and religiously fundamentalist, though subject to some variations and even divisions in both respects; and

- Second, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) – a privileged, influential and separate section of the country’s armed forces – which is religiously underpinned and geared to heavy involvement both in Iran’s economy and in the affairs of countries in the region. It also has some internal security responsibilities and, importantly, command of Iran’s missile forces.

Both of these groups relish religiously-charged confrontation with the US through proxies, as seen in conflicts with Israel in Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria. And they are using the current situation as the setting for just such confrontation.

Besides, military cooperation with Moscow is increasing: witness the role both of Iranian ballistic missiles and of new versions of Iran’s Shahed drones in strengthening the Russian military’s position and constraining the Ukrainian army’s advance. And this provides both an outlet and a testing ground for the products of a defence industry that might otherwise be impossible for Iran’s ailing economy to support. So it suits the dominant interests just fine. Recent revelations about Russia paying for these drones in gold bullion highlight Kremlin’s desperation for advanced weaponry and inability to procure it through traditional channels.

This situation presents a double-edged sword for Iran. On one hand, the country secures an avenue for its defense industry’s products and gains a testing ground for new military technology. On the other hand, it brings to light the shortcomings of the Russian arms industry, which would fail to meet the army’s requirements without imports. Should Russia face defeat, Iran might find itself burdened with a military sector it cannot afford. Conversely, if Russia emerges victorious or negotiates a favorable deal with the West, the Ayatollahs must grapple with the unsettling prospect of being enticed and subsequently abandoned, left as a redundant third party.

Cooperation, to be sure, isn’t confined to the military sphere. Energy cooperation between Russia and Iran is flourishing. But the true extent of its benefit to Iran remains debatable. To put it mildly, Russia has problems of its own. Its technological and financial dependence on the West is evidenced by delays to its Arctic LNG project. And its oil and gas production is declining, which suggests growing problems with production and sales. So it’s unclear how much of substance Russia can offer Iran in the way of technology or resources. And it’s even less obvious how it can help Iran place its oil and gas exports abroad when it can’t sell its own fuels.

But, above all, what Iran definitely doesn’t want is direct military confrontation with the US.

The country’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, has said so explicitly and, though that in itself is no reason to believe him, it’s entirely plausible. Direct conflict is something that Iran could not win, and would very likely lead to the end of the Islamist regime in Tehran – even though victory for the US would not be easy and might prove Pyrrhic both in its achievement and in its sequel. But recent events, perhaps those in the Red Sea even more than those in Gaza, have greatly increased the risk of such direct conflict.

If you like this article, please support us with a donation to PayPal and to the direct account of the association Alternatives and Analyses IBAN BG58UBBS80021090022940. This will ensure that there will be further analyses

In fact, there’s even more to it than that – or we can, at any rate, be a little more precise.

In its dealings with Russia, Iran’s primary objective is to prevent direct Russian control over Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis. This ensures that Iran maintains influence over these groups, avoiding entanglement in foreign conflicts where Tehran itself doesn’t set the agenda. The prospect of a US withdrawal from Iraq and Syria remains a contentious issue, with uncertain implications for the region. Iran aims to retain the key to regional conflicts, using its non-state actors as proxies, but seeks to avoid a major war, the consequences of which Tehran would bear the brunt, and not Moscow. The conflicts in Gaza, the Red Sea, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon are viewed by Iran’s rulers as part of a complex strategic standoff and without immediate existential urgency for the regime.

But Russia’s interests are significantly different from Iran’s. At present, Mr Putin’s immediate goal is to escalate aggression and draw the US and the West into direct regional involvement, diverting attention from Ukraine. This aligns with the life-and-death significance of the Ukraine war for the man in the Kremlin, potentially to an apocalyptic extent.

So, to the extent that it’s Moscow which is taking the initiative, one may presume that Tehran is displeased for two main reasons:

- First, the Kremlin might be breaching Iran’s carefully guarded monopoly of control over proxies.

- Second, Russia is trying instigate a wide-ranging regional military conflict, an outcome that Tehran fears – and that the established monopoly is designed to prevent. Which is especially irksome because said conflict is being set in motion for the sake of Russian victory in Ukraine, a cause that the Ayatollahs and the IRGC don’t consider crucial.

To sum up, a façade of close relations between Moscow and Tehran probably mask present tensions and even greater potential divergences. Russia has less than it might seem to offer Iran. And Iran is very likely alarmed at Russia’s wayward activities in a region where Tehran itself aspires to be the dominant power.

Chairman Xi steps in

As for China’s role in the Russia-Iran equation, according to a recent Reuters report, Chinese officials have asked their Iranian counterparts to help curb attacks on ships in the Red Sea by the Iranian-backed Houthis or risk damaging business relations with Beijing. In other words, China is pressing Iran to help mitigate the mayhem that Russia is instigating.

The activation of the Houthis may, in fact, be curiously linked to a project that looms large in Mr Putin’s policy towards Beijing. For some time now, he has been trying in vain to secure China’s approval for the grandiose Power of Siberia 2 (PS-2) project – also known as the ‘Altai gas pipeline’. This would be a 2,500-km pipeline linking Russia’s Altai gas fields in western Siberia to the energy-hungry Chinese market, creating a route analogous to Nord Stream 1, which carried gas westwards to Germany.

Mr Putin now needs PS-2 more than ever. Developing the European gas market had taken Russia nearly 50 years of patient work. Yet, less than two years into the Russian leader’s reckless Ukrainian adventure, it has all but vanished. So Mr Putin is in desperate need of somewhere else to sell his gas.

But Chinese leader Xi Jingping is, at minimum, playing hard to get and may just not be interested in helping the Russian leader out. Despite Mr Putin’s persistence, Mr Xi is reluctant to commit hastily either to annual purchases of 100 bcm of gas (70 bcm more than current levels) or to financing the $13.6 billion project. The Chinese leader is proceeding cautiously, avoiding overreliance on Russian natural gas supplies – seemingly learning lessons from the experience of Germany and its former chancellor Angela Merkel.

Which is why some experts, with a certain plausibility, interpret the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea as Moscow’s subtle message to Beijing that land pipelines are more secure than sea routes. And maybe even, also, the Kremlin’s way of suggesting that vulnerability could extend to Chinese seaborne exports to Europe and the Atlantic coast of North America.

Incidentally, pipelines may not be the only card in Mr Putin’s hand. Complications in the Red Sea could make the northern Arctic sea route from East Asia to Europe more attractive to Beijing as a way of getting its exports to the EU safely and relatively quickly, which would suit Mr Putin geopolitically. For, if Mr Xi should decide that he wants to use the Arctic route, the fact that Russia has a whole fleet of icebreakers on hand – while China has none – would be a powerful argument for keeping Mr Putin sweet. The route’s prominence could also help the Russian leader sell more gas, as it could be used to deliver LNG from the growing liquefaction capacity of Russia’s Yamal gas field on the north coast of Siberia.

But if Mr Putin is using the Houthis to drop a hint, it’s another matter whether Mr Xi will take it. As things stand, the Red Sea route is pivotal for China’s exports to Europe and North America as well as for crude oil exports from Saudi Arabia and the Gulf that are destined for China: it’s hardly accidental that the only overseas naval base Beijing has in the entire world is in Djibouti, at the entrance to the Red Sea.

The fact that alternatives to the Red Sea route could, if necessary and eventually, be found does not mean that Mr Xi will be happy at being reminded of this – or at the inconvenience and cost of said reminder. As Chinese economic growth falters and Mr Xi grapples with the lingering economic aftermath of his debatable approach to dealing with COVID-19, the last thing he needs is economic instability and a global trade slowdown.

Nor, perhaps, may Mr Xi welcome Mr Putin’s encouragement of his tiresome next-door neighbour Kim Jong Un, dictator of North Korea.

It’s not just that the Russian leader eggs Mr Kim on to fiery anti-Western rhetoric: he’s done that for some time. The problem is that the Russian leader has lately given edge and specificity to Mr Kim’s threats by advanced military technology transfers. That suits Mr Putin for two reasons:

- First, he gets hardware and munitions supplies in return.

- Second, it’s convenient to have someone other than himself talking up the explicit threat of nuclear war.

But unpredictability and incendiary threats in his own back yard hardly serve the Chinese leader’s purposes.

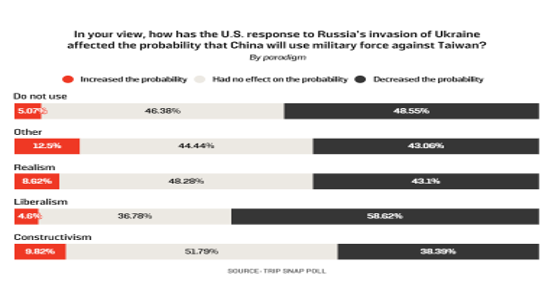

As for the likelihood that any firm US or Western support in Ukraine could be used by Russia to tempt China into launching its own ‘special operation’ against Taiwan, thus adding a new geopolitical point to the frontline between the West and Russia, and generally the extent of the impact of the war in Ukraine on Beijing’s policy towards Taipei, a recent survey of the expert community published in Foreign Policy effectively denied such a direct and proportional link. China has its own list of priorities, and Mr Putin has little chance of dictating to Chairman Xi how and when to confront the US.

The case of India

India, like China, is heavily reliant on the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. That is especially true for its exports – specifically in respect of Indian goods’ access to the EU and to North American markets.

Now, this could change, if and when the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) project is realised. A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for this was signed in September 2023. A rival to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, IMEC would bypass Suez by providing a route via Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and thence, by way of Jordan and Israel, to Greece and the EU.

But realisation of that project will take years, and meanwhile India is stuck with Suez. New Delhi, moreover, may be vexed that IMEC’s implementation is currently on hold, given hostilities in Israel – vexation that is quite likely to be directed in part at Moscow.

In terms of imports, India’s oil flows are only partly through Suez and the Red Sea, as the Arabian Gulf is the source of much of its oil. However, as noted above, the crude oil that India receives from Russia comes via the Red Sea, and this is very important for New Delhi at the moment, as this oil is both plentiful and cheap, thanks to the Western embargoes imposed since the invasion of Ukraine. More importantly, products derived from Russian crude that is refined in India are mostly sold in Europe, having been shipped there from India through the Red Sea and Suez.

India may perhaps be grateful to Moscow in some superficial sense for this oil. But, to be cynical, the predominant emotion is more likely to be quiet glee that the Russians have no choice but to offer a very good deal. Meanwhile, there is presumably vexation again: in this case, at the fact that, with its activities in Yemen, Russia is simultaneously making this forced largesse more precarious.

And it’s worth noting that, even when it comes to oil, things are far from harmonious between Russia and India.

Until recently, Russian oil had been especially attractive to India because it had been able to pay for much of it in rupees rather than dollars. But the intergovernmental agreement to this effect broke down, in practice, in the final months of 2023, with the Russians demanding Chinese yuan and the Indians preferring UAE dirhams. The problem was that the Russians had accumulated more than $40 billion in rupees equivalent at the official exchange rate from crude oil exports, while India’s trade deficit is set to exceed $39 billion in fiscal year 2023/24. And, to say the least, Russian traders prefer Chinese goods to Indian ones.

Result: as of end-January 2024, 14 tankers full of Russian oil were reportedly stuck in Indian ports waiting to be unloaded as the payment stalemate continued, while others originally destined for India were diverted on a wild goose chase to find dollar buyers in non-Indian ports, presumably at very deep discounts.

The moral of the story is, potentially, two-fold:

- First, that cosy and fraternal bilateral arrangements don’t go very far in solving Moscow’s problems – and that the Indians know how to drive a hard bargain.

- Second, that Mr Putin would be generally ill-advised to rely on fantasies about doing without the dollar or the euro. Russia isn’t much interested in rupees and apparently India isn’t much impressed with yuan. But even should New Delhi warm to the Chinese currency, one possible reading of Mr Putin’s troubles with Chinese bank CZCB (see above) is that the yuan may not be on offer much longer as a means of international payment among “friends”.

In terms of geopolitics and alignment, Russia would like to see India as “anti-Western”. But a more accurate description would probably be “assertive” towards all and sundry, including the West and various individual Western countries. And the BRICS’ claim to be an “anti-Western bloc” – or any bloc at all – is undermined by the biggest antagonism within it: the traditional rivalry and mistrust between India and China.

Economically, India’s orientation is now predominantly to the West. A Free Trade Agreement with the EU is in the offing, with optimists talking of its possible conclusion this year; things are less advanced with the US, but there’s an atmosphere of growing cooperation, gradual resolution of issues, and progress. Both the US and the EU, as well as some key EU states, were signatories of last year’s MOU for IMEC. And a large and very successful diaspora of first- and second-generation Indians in the West – including a British prime minister, a US vice-president, and a host of tech specialists – no doubt informs attitudes and aspirations in general, if not policies in detail. Meanwhile, India is gradually replacing China as the prime destination for foreign direct investment from the West, and has already overtaken its old rival as an importer of crude oil (as well as in population).

Next, India’s old ties with Russia – dating back to Soviet days – surely count for little now, with transactional calculations of immediate advantage probably governing both sides’ actions. Oil aside, Russia’s status as a major arms supplier is a tie that still binds to some extent. But even that has been subject to some dilution, while much scepticism has no doubt resulted from what has, to put it mildly, been a mixed performance of Russian weapons during the Ukrainian war – which should have served as a showcase and a sales opportunity.

That goes both of the more established, run-of-the-mill Russian armaments and of much-hyped cutting-edge weapons. The last few months have been especially anti-climactic for the latter. The vaunted Kinzhal missile, which was supposed to be impossible to shoot down, has proved anything but. And the much hyped S-400, or the new Armata tank that has been conspicuously absent from the battlefield, while the multi-role export-grade Su-57 fighter hasn’t been seen at all in Ukrainian airspace.

Moreover, just now Moscow needs for itself all the military hardware and spares it can produce. That puts a question-mark over how far New Delhi, in the turbulent times ahead, can rely on priority, or even normal, treatment. And it’s not just the Indians that will be taking notice of all this.

Finally, Moscow’s heavy reliance on North Korea and Iran for military supplies is probably not good for the image of its defence industry in India and elsewhere.

The latest revelation of how desperate the once-proud Russian arms industry has become is the recent payment in gold, mentioned above, for 6,000 Iranian Shahed drones. Procurement from North Korea actually makes good sense, given the frighteningly high rate at which ammunition is being consumed and the emerging role of cheap and relatively low-tech platforms such as drones. But having such states as major suppliers doesn’t look good. Not for a country that claims to have a world-class defence sector.

In short, India is driving towards growth and aspiring to prosperity and greatness on the international stage, and has specific uses for Russia rather than a general alignment. It’s unlikely to have much patience with anything that gets in the way of that drive. Moreover, it’s especially unlikely to cut Russia much slack when it engages in economically disruptive and politically destabilising antics on its main trade routes. Particularly if said antics involve radical Islamism. And particularly as Moscow is so cosy with New Delhi’s historic rival Beijing.

In the third and final part of this analysis, we will look at other countries that Russia might hope to rely on in its global war against the West – and the chances that these countries will in fact play ball with Mr Putin.